The Sweet Track is an ancient Neolithic wooden trackway, constructed as a single-plank elevated walkway spanning nearly 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) across the reedswamp that stretches between the Polden Hills and the island of Westhay, in the Brue Valley west of Glastonbury, Somerset.

It was discovered in 1970 by Ray Sweet, a peat digger after whom the trackway is named. Alongside the trackway, a diverse array of Neolithic artifacts has been found.

These include polished stone and flint axes, flint arrowheads, fine pottery, and various organic items such as a wooden bowl, a toy axe, yew pins, a potential bow, a stirrer, and a digging stick.

The discovery of high-quality burnished pottery and a handle-less polished jadeite axe from the Alps indicates that there was likely a practice of making deliberate votive offerings near the trackway. The Sweet Track is recognized as the earliest structure in the UK associated with such ritual activities.

Contents

Discovery

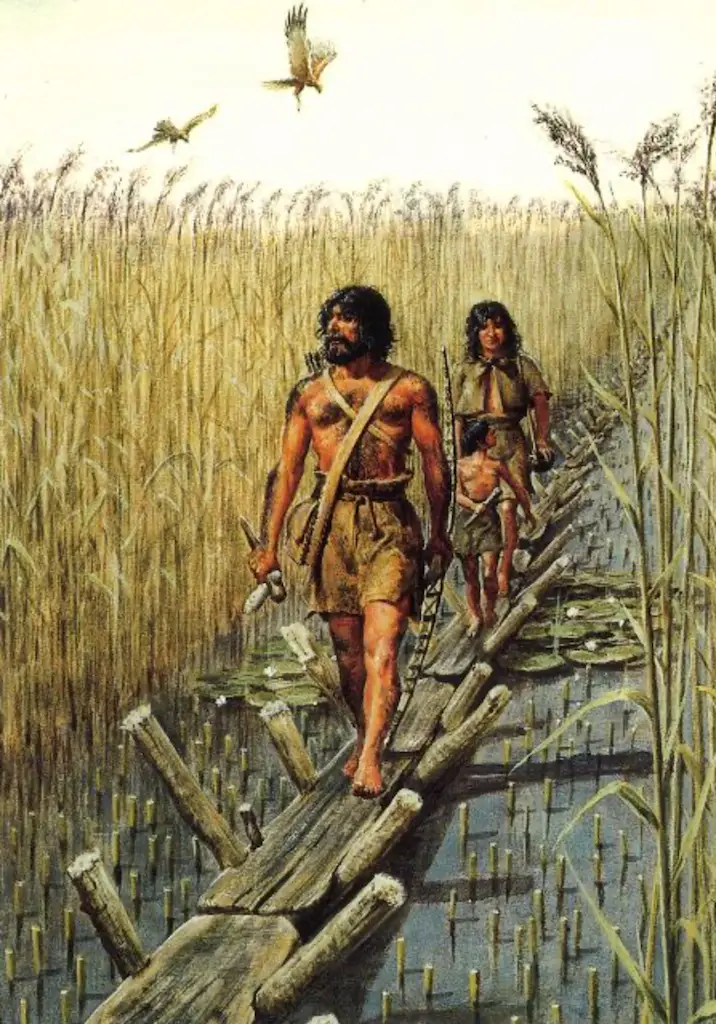

Imagine the Neolithic people coming together for a major community effort: days and nights spent planning, designing, and collecting materials for a construction project.

Picture a specific day, perhaps a Thursday, when an individual, whose name has long been forgotten, is out in the marsh, driving stakes into the ground to create a pathway that would connect towns.

Read More: Peoples Have Been Roaming our Countryside for 900,000 Years

This was as real and tangible as the world we live in today, under the same sun that cast their shadows on the ground. They would take breaks, share laughs over jokes, wrap up for the day, and head home for dinner, planning to return the next morning to continue their work on the track.

Fast forward 5,830 years, and imagine a distant descendant today catching a brief glimpse of this ancient endeavor in the form of a photograph.

This image, transmitted across the globe through invisible currents of electricity and radiation, represents a stark contrast to the world of its creators. T

o those ancient builders, our modern existence would seem utterly alien and unimaginable, yet in many ways, the ordinary tasks and rhythms of their lives bear a striking resemblance to our own.

Somerset Levels

The Sweet Track, nestled in the Somerset Levels of England, serves as a testament to the ingenuity of Neolithic engineering. This ancient trackway was discovered quite unexpectedly in 1973 by a local peat cutter named Ray Sweet, lending his surname to this significant archaeological find.

Read More: Prehistoric Burnt Mounds, What are They?

The Somerset Levels, an area rich in historical and environmental interest due to its extensive wetland ecosystem, have preserved a variety of ancient artefacts and structures remarkably well, thanks to the anaerobic conditions of the peat bogs.

Prior to its discovery, the significance of such trackways was not fully appreciated, largely because many lay hidden beneath layers of peat, undisturbed for millennia.

The Somerset Levels have historically been prone to flooding, and over centuries, local communities adapted to the challenging landscape in innovative ways.

Read More: Oakley Down Cemetery 6000 Years of History

The Sweet Track is a prime example of this, having been constructed during a period when the rising water levels in the wetlands necessitated a durable and elevated pathway.

The initial discovery of the Sweet Track was followed by extensive archaeological investigations that unveiled its structure and extent.

Radiocarbon Dating

Through these excavations, it was determined that the track was built around 3800 BC, making it one of the oldest known wooden trackways in Northern Europe. The construction technique involved cutting down oak trees, splitting them, and laying the planks end-to-end to form a straight route across the marshes.

Radiocarbon dating of the wood confirmed the track’s age and provided insights into the advanced capabilities of the early settlers in the area.

Read More: What Exactly is a Forest, it Doesn’t Mean Trees

Researchers found that the construction of the track was likely a response to a particularly wet phase in the region’s history, which made daily tasks and transportation increasingly difficult.

The trackway facilitated movement across the wetlands, improving access to different parts of the landscape for hunting, gathering, and possibly trading.

The discovery of the Sweet Track significantly enhanced our understanding of Neolithic life and mobility in the Somerset Levels.

It highlighted the early human adaptation to changing environmental conditions and underscored the complexity of prehistoric communities in Britain. The track not only served a practical purpose but also stands as a symbol of human resilience and innovation in the face of natural challenges.

Read More: First Fleet Convicts Transported to Australia

Its uncovering has since propelled further archaeological interest and exploration in the region, leading to the discovery of more trackways and a deeper appreciation of the area’s prehistoric past.

Sweet Track Construction

The construction of the Sweet Track was a feat of considerable engineering prowess, reflecting the sophisticated understanding of materials and environment possessed by the Neolithic inhabitants of the Somerset Levels.

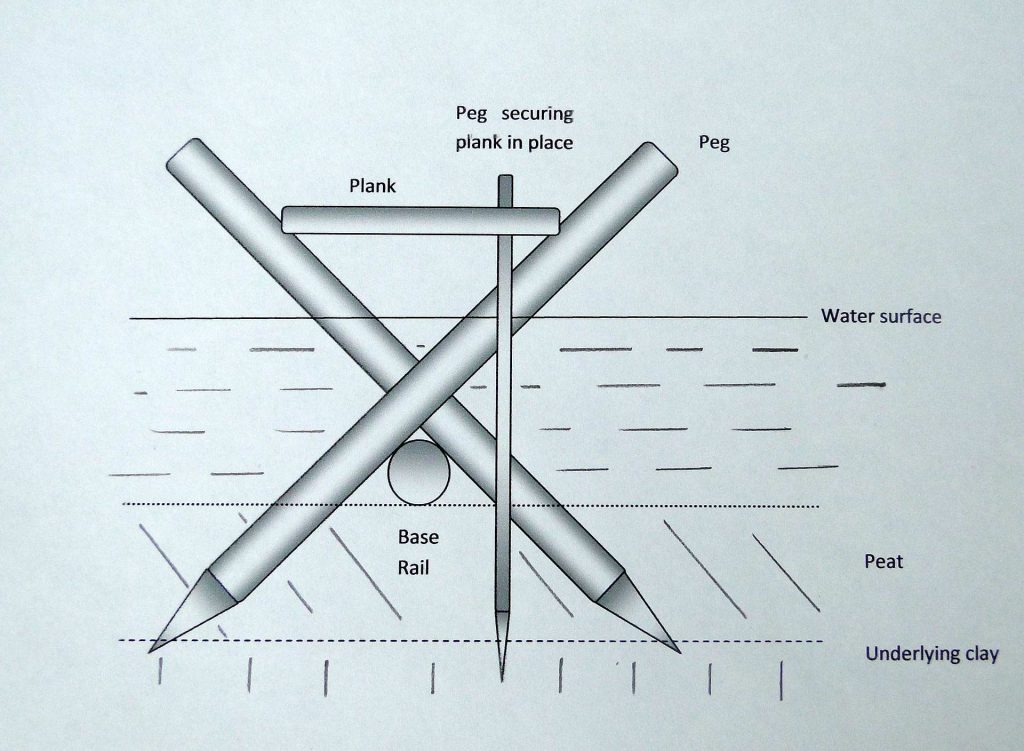

Constructed in either 3807 or 3806 BC, the Sweet Track was an ingeniously designed walkway primarily composed of oak planks laid end-to-end, supported by pegs made from ash, oak, and lime.

Read More: The Critical Role of Medieval Hiring Fairs in England

These pegs, driven into the peat beneath, helped stabilize the structure. The oak planks used were impressive, measuring up to 40 centimeters wide, 3 meters long, and less than 5 centimeters thick, sourced from trees that were up to 400 years old and 1 meter in diameter.

These trees were felled and split using only stone axes, wooden wedges, and mallets, showcasing remarkable Neolithic craftsmanship.

The construction technique involved laying longitudinal log rails, primarily made of hazel and alder, up to 6.1 meters long and 7.6 centimeters in diameter, across the laid pegs.

Read More: What are Cross Dykes?

The pegs were angled across these rails into the peat base, and notches were then cut into the planks to accommodate these pegs, forming the track’s walkway. In certain sections, a second rail was added atop the first to level the adjacent plank with the rest of the walkway.

Components of the Sweet Track

Some planks were further stabilised with slender, vertical wooden pegs driven through pre-cut holes into the peat or clay below. Towards the southern end, smaller trees were utilised, with planks split across the grain to use the full diameter of the trunks.

Fragments of other tree species such as holly, willow, poplar, dogwood, ivy, birch, and apple were also discovered along the track.

Read More: What is an Anglo-Saxon Moot?

Indications are that many components of the track were prefabricated and brought to the site for assembly, though evidence of wood chips and chopped branches suggests that some finishing work occurred on-site.

The total timber used in the track’s construction weighed approximately 200,000 kilograms, yet estimates suggest that ten men could have assembled it in just one day.

Read More: Avebury Henge, Largest Megalithic Stone Circle in the World

The track was operational for only about ten years before rising water levels likely submerged and rendered it unusable. The range of objects found alongside the track points to its regular use in the daily farming activities of the community.

Older Post Track

Since its discovery, it has been revealed that parts of the Sweet Track were built over an older pathway, the Post Track, which dates back to 3838 BC, further emphasizing the area’s historical significance and the continuity of pathway construction techniques over generations.

Archaeological analysis shows that the construction was likely a planned, community effort, indicating a well-organized society with the ability to mobilize labor and resources for large projects.

Read More: Old Sarum a Norman Power Base

The design of the trackway also demonstrates an understanding of the landscape and hydrology of the Somerset Levels, as it was built to withstand the particular conditions of the wetlands.

The primary purpose of the Sweet Track was to facilitate movement across the waterlogged peat bogs, which were difficult to traverse for much of the year due to flooding.

The track provided a raised, stable path that enabled easier and faster travel between areas that were seasonally cut off from each other. This would have been crucial for maintaining social and economic connections between different communities, allowing for the exchange of goods, services, and information.

Read More: Meare Heath Trackway: A Bronze Age Structure

Furthermore, the construction of such a trackway may have had significant social and symbolic implications. It could have served as a communal pathway, reinforcing bonds within and between groups, or possibly demarcating territories.

Profound Insight

The archaeological findings associated with the Sweet Track provide a profound insight into the Neolithic era in the Somerset Levels.

Upon its excavation, archaeologists discovered a range of artefacts that shed light on the daily lives, technologies, and environmental interactions of the communities that built and used the trackway.

The types of artefacts recovered include tools made from stone and bone, remnants of pottery, and personal ornaments, which together suggest a well-established, resourceful community capable of skilled craftsmanship and trade.

Read More: Roman Roads of Britain, The Ancient Highways

Among these findings, flint tools stand out due to their sophistication. These tools likely served various purposes, from hunting and food preparation to woodworking and other crafts.

The presence of such tools along the track suggests that it was not only a route for travel but also a site for diverse activities, possibly including trade and social gatherings.

One of the most significant finds was the wooden artefacts preserved by the anaerobic conditions of the peat. These include items such as paddles, bowls, and parts of small boats or canoes. These items are particularly valuable as organic materials rarely survive from this period in other contexts.

Read More: The 4,300 Years Old Amesbury Archer ‘King of Stonehenge’

The wooden objects provide a rare glimpse into the more perishable aspects of Neolithic technology and daily life, which are often lost in the archaeological record.

Additionally, environmental data gleaned from the site has been invaluable. Pollen analysis has revealed changes in the local vegetation over time, indicating how the Neolithic people may have managed the land.

Woodland Clearence

The presence of certain species of pollen suggests areas of woodland clearance and the possible cultivation of crops, which complements the evidence of settled agricultural practices suggested by other artefacts.

Furthermore, the track itself, in its construction and layout, offers significant insights. Its careful design and the method of its construction reflect a sophisticated understanding of the local environment and hydrology.

Read More: Roman Forts Still Litter Our Countryside

The choice of materials, the construction techniques used, and the scale of the track indicate a high level of organisational ability and social cooperation among the Neolithic population.

The artefacts and environmental data combined paint a picture of a dynamic Neolithic society, capable of complex construction projects and sustainable landscape management. Often is the thought that they were some primitive society, but they were anything but.

This society was not only adapting to its environment but actively shaping it. Each artefact and piece of ecological evidence adds to our understanding of how these ancient peoples lived, worked. We are lucky to have such finds.

Environmental Study

The environmental insights gleaned from the study of the Sweet Track in the Somerset Levels offer a fascinating glimpse into the Neolithic landscape and how it was managed and manipulated by ancient societies. These insights are crucial for understanding the relationship between environmental changes and human adaptations over thousands of years.

The Somerset Levels, an area characterised by its wetland ecosystem, presented unique challenges to the Neolithic inhabitants.

Read More: A Megalithic Mystery: What Are Dolmens?

Archaeological studies of the track and surrounding areas provide evidence of water level management and landscape modification that was necessary for survival and mobility in such an environment.

Pollen analysis conducted around the Sweet Track site has revealed significant information about the vegetation patterns and climatic conditions of the time.

This analysis indicates that the area underwent considerable woodland clearance, which suggests deliberate landscape management. Such activities likely facilitated agriculture, including the cultivation of early forms of wheat and barley, which in turn supported a growing population.

Plant Matter

The variations in pollen also suggest a dynamic interaction between human activities and climatic changes. For example, shifts in the types of plant species and the proportions of arboreal to non-arboreal pollen grains offer clues about periods of agricultural expansion or reforestation, which may have been responses to climatic fluctuations.

Moreover, the preservation conditions in the peat bogs of the Somerset Levels have allowed for exceptional organic preservation.

Read More: Uncovering the Secrets of Prehistoric Henges

The materials found, including wood and other plant matter, not only inform about the construction materials available and chosen by the Neolithic people but also about the broader environmental conditions.

For instance, the types of trees used in the construction of the Sweet Track indicate the composition of local woodlands and the selection strategies employed by ancient builders to utilize resources sustainably.

Studies of the submerged forests and peat layers have further enhanced understanding of sea-level changes and their impacts on Neolithic communities. These studies show that the people of the Somerset Levels were continually adapting to a landscape that was itself in flux.

Read More: Doggerland, The Prehistoric Land Swallowed by the Sea

The environmental record shows the Neolithic people were not merely passive dwellers in their environment but active managers of their landscape.

Sweet Track and Social Implications

The cultural and social implications of the Sweet Track extend far beyond its practical use as a thoroughfare through the challenging marshlands of the Somerset Levels.

The construction and maintenance of such an elaborate structure during the Neolithic period suggest significant organisational skills and a complex societal structure capable of planning and executing large-scale projects.

Read More: Neolithic Boulder of National Importance Found in Dorset

The Sweet Track was not just a feat of engineering; it was a manifestation of the collective effort and social unity of the community. This level of coordination and cooperation likely required some form of social hierarchy or leadership structure, indicating a sophisticated social organisation.

The route likely played a role in seasonal rituals or gatherings, which would have strengthened communal ties and shared cultural identities.

These gatherings would have been opportunities for exchanging not only goods but also marriages, allegiances, and knowledge, thus reinforcing social networks and cohesion. The track’s role in these activities would have imbued it with a cultural significance that extended beyond its immediate practical utility.

Read More: The Story of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

Furthermore, the decision to invest substantial resources into building a permanent structure like the Sweet Track suggests a deep relationship with the landscape, possibly reflecting a worldview that saw the environment as something to be actively managed and cared for.

This relationship might have been reflected in ritual or religious practices, perhaps involving the track itself.

The presence of high-quality artefacts and materials from distant regions, as found near the Sweet Track, indicates that the people of the Somerset Levels engaged in wide-ranging trade networks.

The track facilitated these interactions, which would have brought not only material benefits but also cultural exchanges, introducing new ideas, technologies, and beliefs that could have transformed local societies.

Sweet Track Preservation

Much of the Sweet Track remains in its original location, now part of the Shapwick Heath National Nature Reserve and Site of Special Scientific Interest.

Read More: Ackling Dyke: A Significant Roman Road?

Following the acquisition of the land by the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the installation of a water pumping and distribution system across a 500-metre section, several hundred metres of the track are actively preserved.

This preservation method, which involves maintaining a high water table to saturate the site, is uncommon for wetland archaeological sites. A specific 500-metre section within land managed by the Nature Conservancy Council is encircled by a clay bank to inhibit drainage into the surrounding lower peat fields, and water levels are closely monitored.

This preservation approach has proven effective when compared to the nearby Abbot’s Way, which, without similar treatment, was found to be dewatered and desiccated in 1996.

Read More: Danelaw and the Rise and Fall of England’s Viking Kingdom

The maintenance of water levels at Shapwick Heath involves collaboration between the Nature Conservancy Council, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, and the Somerset Levels Project.

Although the wood recovered from the Levels appeared visually intact, it was extremely degraded and very soft. Where feasible, pieces of wood in good condition or the worked ends of pegs were removed for conservation and later analysis.

Sweet Track Segment

The conservation process included keeping the wood in heated tanks filled with a polyethylene glycol solution and gradually replacing the water in the wood with wax through evaporation over about nine months.

After this treatment, the wood was removed, wiped clean, and as the wax cooled and hardened, the artifacts became stable enough to be handled freely.

Read More: Danelaw and the Rise and Fall of England’s Viking Kingdom

A segment of the track on land formerly owned by Fisons, a company that extracted peat from the area, was donated to the British Museum in London.

Although this section can be assembled for display, it is currently stored off-site under controlled conditions.

A reconstructed section was displayed at the Peat Moors Centre near Glastonbury, operated by the Somerset Historic Environment Service until its closure in October 2009 due to budget cuts by Somerset County Council. The main exhibits still exist, though future public access remains uncertain. Additional samples of the track are preserved in the Museum of Somerset.

Designated as a scheduled monument, sections of the track are recognized as “nationally important” historical structures and archaeological sites, protected against unauthorized alterations.

These sections are also listed in Historic England’s Heritage at Risk Register, emphasizing their significance and the need for ongoing protection and management.